In 1793, a yellow fever epidemic hit the city hard, and sent George Washington and the federal government packing.

On Sunday, September 1, 1793, Samuel Powel, Speaker of the Pennsylvania Senate, penned a hurried note to Dr. Benjamin Rush, asking his opinion on a spreading “putrid fever” making its way through the city of Philadelphia. A prominent local physician and politician, Dr. Rush was considered the foremost expert on the matter. The previous month, Powel and the rest of the legislature watched as the fever rampaged through Philadelphia, a city of nearly 50,000 residents. Powel inquired if “the putrid Disorder which has so much alarmed the City is abating or increasing.” If the former were the case, public business would go on as usual. If the latter, the state legislature would adjourn immediately. Two days prior, another legislative member noted in his diary that “a young man by the name of Fry is lying dead at the west end of the State House.” At the time of Powel’s writing, the city had already lost nearly 300 people to the fever, but the news so close to home was the likely tipping point leading to Powel seeking Dr. Rush’s advice. In the following days, the government would shut down and the streets would empty. By the end of the outbreak two months later, the city would lose more than 5,000 of its 50,000 residents.

The population of Philadelphia steadily grew throughout the late 18th century, as it continued operations as a booming port city and served as the temporary seat of the federal government from 1790 to 1800, via the Residence Act signed by George Washington. Docks packed the Delaware River along Water Street, the main thoroughfare. Large townhomes spread far into the western side of Philadelphia, populated by members of the government, including George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson. Wealthy families of the city—among them the Shippens, the Chews, the Penns, and the Powels—also resided in these homes. The residents of the city experienced an unseasonably warm spring and summer of 1793. The drought of summer meant low water in the river, and the slimy banks lay exposed. Merchants operated their trading business year-round, bringing in goods from across the world. The transatlantic trade, while a necessity to the economy, often brought disease when ships docked in the city. Because of this, as with many port cities, yellow fever was not a new occurrence. One citizen wrote that it was “deplorably certain as to the reality of existence.” However, due to the infrequency of major outbreaks, the disease made little political impact. The last major outbreak of the fever had occurred in 1762, so it was not on the forefront of people’s minds. That changed in late July.

A sloop docked at the wharf at the edge of Arch and Water Streets, and unloaded its goods. A load of coffee gone rancid was left sitting near the dock. The streets that bordered the wharves were cramped and narrow. As the foul, humid air of summer and rotting coffee lay stagnant between the homes, residents near the dock started falling ill. Dr. Rush was the first to treat these patients, and recognized the classic symptoms of yellow fever, which he had last seen as a young doctor’s apprentice in 1762. He targeted the “noxious fumes” from the coffee as the initial carrier of the disease, due to the coffee’s proximity to the infected patients. The disease quickly spread in all directions, increasing the doctor’s need to find methods to save as many citizens of Philadelphia as possible by tracking and containing the illness.

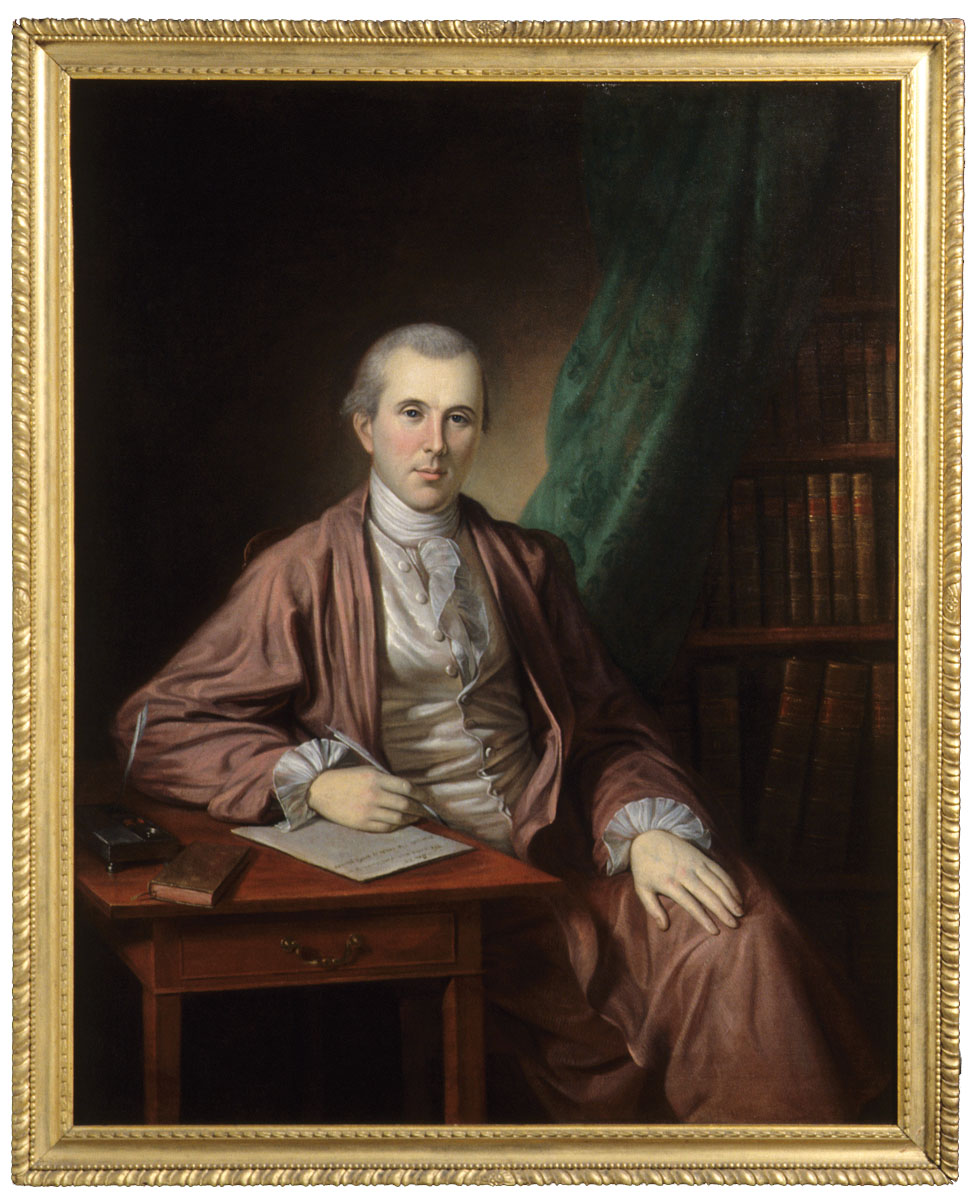

Benjamin Rush was a leading medical professional in Philadelphia throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries. He served as the surgeon general of the Continental Army, and in a number of political and philanthropic roles within the federal government and city of Philadelphia.

Dr. Benjamin Rush, Charles Willson Peale, 1783–1786 (Winterthur Museum Collection)

By the end of August, Rush understood that the fever had overrun the city. Severe precautions were set by the local government, which included adopting “bizarre amulets” to ward off the disease. Those who either chose to stay, or had no way to leave, followed unproven herbal remedies such as smoking cigars, burning gunpowder, chewing garlic, and wearing tar-covered ropes around their necks. They avoided one another on the streets, covered their mouths with cloth, and kept their heads down.

Those with the means to do so (an estimated 20,000) fled the city, many leaving their homes vacant to shelter at country estates. The city’s crowded streets suddenly emptied. Dr. Rush and a committee of 16 fellows from the city’s medical society, the College of Physicians, met to discuss treatments for the fever. The committee could not come to a consensus on how best to combat the disease, a disagreement which carried over from past breakouts of the epidemic. With his seniority, Rush prevailed, insisting on bloodletting as the best cure. Medical intervention did not stop the deaths from piling up, and church bells tolled endlessly, marking each death.

In the 18th century, health, safety, and welfare practices fell under the operations of local governments. Though the federal government resided in Philadelphia, it did not hold power over the local government in this situation, so members had little input on the operations for containing the fever. George Washington’s Cabinet members communicated with representatives from Congress, who were on a scheduled recess, alerting them to the spreading fever.

Although many high-ranking government officials avoided falling ill prior to the move to Germantown, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton and his wife both came down with the fever in early September. Both survived, but it became even clearer that the government needed to leave the city. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson left for their private residences. As the federal government had little say in the operations of the city of Philadelphia, many members chose to preserve their health. The day before George and Martha left, the couple extended a verbal invitation to their close friends Samuel and Elizabeth Powel to leave the city with them. Elizabeth wrote a letter back to “her dear Friend and very dear Madam,” that even “at this awfull Moment,” she and Samuel would stay in Philadelphia, as “Mr. Powel saw no Propriety in the Citizens flying from the only spot where Physicians conversant in the Disorder that now prevails could be consulted.” The Washingtons sent a kind reply, expressing “regret that in the present instance it will deprive us of the pleasure of your company to Virginia.” Just over two weeks after the Washingtons left for Mount Vernon, on September 29, Samuel Powel died of the disease at Powelton, his farmhouse over the Schuylkill River.

On October 1, Oliver Wolcott, a government official, sent a list to the president with the latest round of victims, and mentioned “Mr. Samuel Powel with the more sincere regret.” Powel was the closest friend Washington lost during the epidemic, and the president was deeply affected. Medical professionals such as Dr. Rush continued to see patients, and unsurprisingly, many health providers came down with the illness themselves.

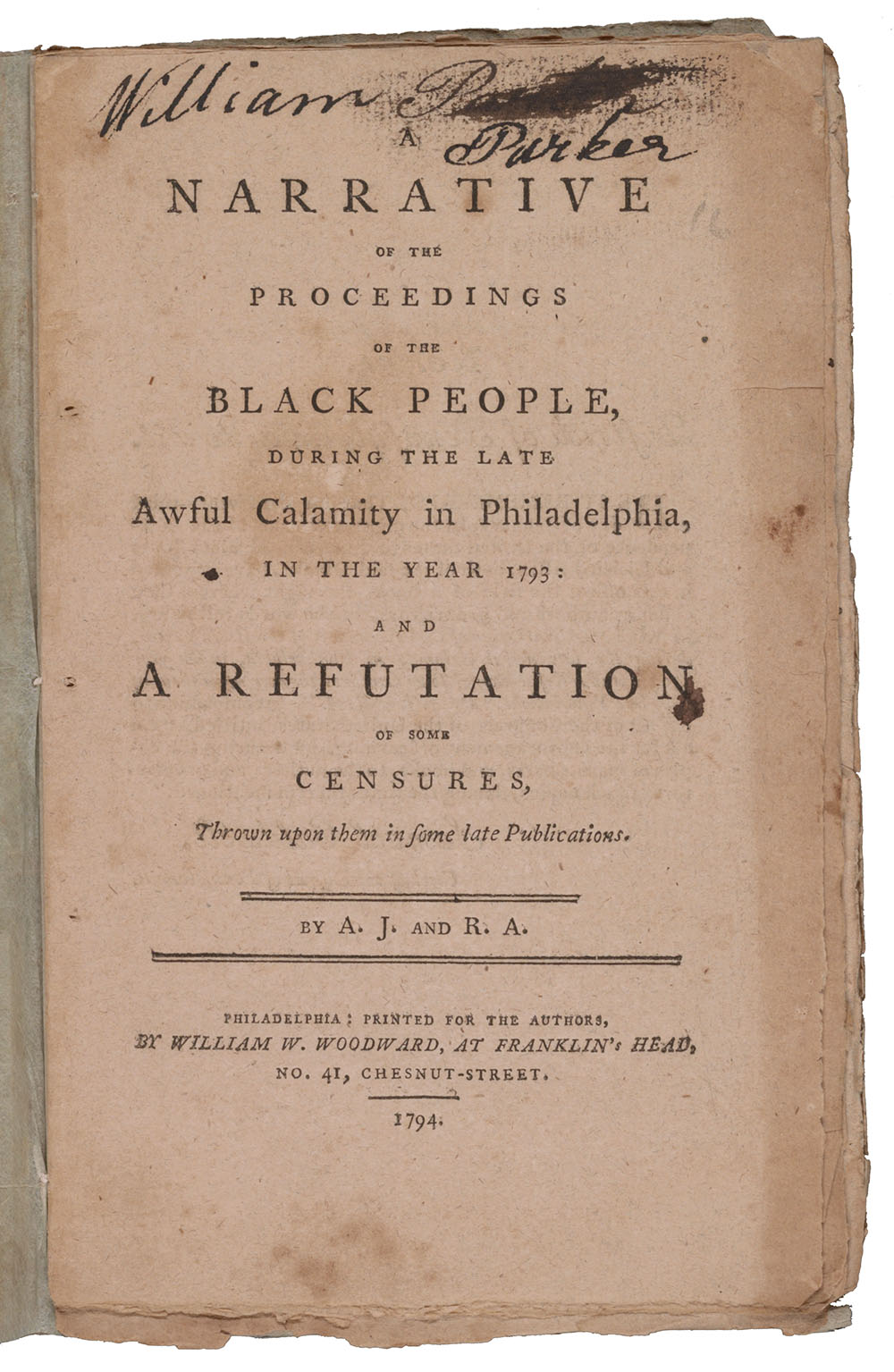

Written by Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, this pamphlet was a response to false claims that the free African American community profited from the yellow fever epidemic.

Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793: and a Refutation of Some Censures Thrown upon them in Some Late Publications (Library of Congress)

In many ways, the free black community of Philadelphia kept the city running during the epidemic. Believing incorrectly that those of African descent were immune to the disease, Dr. Rush pleaded with African Americans to assist with the jobs needed for the maintenance of the city. They worked as “nurses, cart drivers, coffin makers and grave diggers.” Two free black religious leaders, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, wrote in their 1794 publication, Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793: “[A]t this time the dread that prevailed over white people’s minds was so general, that it was a rare instance to see one neighbor visit another, and even friends when they met in the streets were afraid of each other, much less would they admit into their houses.”

Even with the tracing and containing of the illness, the disease began to spread beyond the city limits, toward Germantown. In the first week of October, Speaker John Trumbull and Attorney General Edmund Randolph alerted Washington that the official reconvening of Congress might need to be moved out of Germantown. The president wrote a long letter to Thomas Jefferson on October 11, reflecting on the situation he was now put in. He asked, “[W]hat had I best do? ... Neither the Constitution nor Laws gave power to the President to convene Congress at any other place than where the Seat of Government is fixed by their own act.” Jefferson’s response was straightforward, that even with the spread of the fever, “the Residence law has fixed our offices at Philadelphia till the year 1800 … and therefore it seems necessary that we should get as near them as we may with safety.” Washington followed Jefferson’s suggestion, and likely hoped that the safety of the government would not be put at risk. President Washington officially left Mount Vernon for Germantown on October 28, and when he arrived, he held a number of Cabinet meetings in preparation for the reconvening of Congress.

The committee organized by Mayor Matthew Clarkson continued its work until a frost settled over the city in late November, wiping out the real cause of the outbreak—mosquitoes. However, the nature of the blood-borne disease and its carriers would not be known until nearly one hundred years later. Interestingly, in his journal on September 12, Dr. Rush unwittingly made reference to the “Moschetoes,” which were “uncommonly numerous.”

Though Congress had been poised to reconvene in Germantown, in the end it reconvened back in Philadelphia’s Congress Hall, on December 2. John Adams, on his return to the city on November 30, wrote a letter to his wife Abigail the next day, describing the feel of the recovered city. “May we ever remember, the Thirtieth of November,” he wrote, “because this is the day we were absolved from Infamy … by all accounts, the Pestilence was no more to be heard of.” He noted that “principal Families have returned, the President is here, Several Members of Congress are arrived and Business is going on with some Spirit.” After five months, it was back to business as usual.

Samantha Snyder is reference librarian at the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon and an M.A. candidate in history at George Mason University.

The Arch Street ferry terminal on the Delaware River was a busy waterfront. As the only means of transatlatic commercial transportation, ports brought prosperity but also disease.

Arch Street ferry, Philadelphia,

W. Birch Springland, 1755–1834

(Library Company of Philadelphia)