Amanda Isaac is Mount Vernon’s associate curator.

A Stitch in Time

BOLD, VIVID, FRESH, ABSTRACT, DYNAMIC.

No, we’re not talking about contemporary art at Mount Vernon, but rather piecework quilts made by Martha Washington. Their large size—each one more than eight feet square—and bold patterning are a powerful expression of Mrs. Washington’s creative vision, and an important complement to the popular image of a diminutive, self-effacing, grandmotherly figure. In late 2019, Mount Vernon received the generous donation of a quilt top pieced by Martha Washington, the best documented of only three piecework quilts known to be made by her. Its addition to Mount Vernon’s collection coincides with a new initiative to document, research, conserve, and ultimately exhibit these works of art (see page 7).

Martha Washington’s quilts have been known for decades, but they continue to prompt fresh questions. When did she start quilting? How did she quilt and where? Did anyone help her? What was her skill level and style? Investigating the quilts pieced by the first lady, as well as related quilts from the extended Dandridge, Custis, and Washington families, has the potential to reveal more about her as an individual and many of the otherwise hidden women in her world, free and enslaved.

Then as now, making a quilt began with selecting fabrics, evaluating combinations of patterns and colors, and planning a layout. The fabrics chosen could be repurposed from an old garment, remnants from another project, or purpose-bought new material. Once the pieces for the top had been cut and sewn together, it was time for the quilting itself—the process of stitching together the three-layer sandwich of top, filling, and backing—which distinguishes a quilt from other types of bed covers.

While the piecing might be done primarily by the quilt designer alone, the quilting was traditionally a shared activity, to which relatives and friends were invited. Women gathered for intensive stitching sessions—“quiltings” or “quilting frolics”—and then celebrated with feasting, and occasionally, dancing with both sexes. “Fine eating and merry quilting,” summed up one such event in the life of a young Virginia woman, Francis Baylor Hill, in 1797. Alternatively, quilting might proceed more slowly, with friends and relatives encouraged to contribute whenever they came to visit. In either case, the quilt, with layers basted together and the design marked on its top, was mounted in a rectangular wooden frame with adjustable sides, and then placed table-like on temporary supports. Stitchers gathered around to work. Once the stitching was completed, quilters undid the frame, bound the edges, and sometimes added a decorative fringe. It was then ready for use or display.

There are no known documentary accounts of quilting parties at Mount Vernon, but surviving objects offer important clues. The first of the three quilts, and the only one fully completed by Mrs. Washington, has become known as the Penn’s Treaty quilt, so named because the center depicts “William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians,” a scene from the founding of Pennsylvania in the early 1680s. Considered one of Benjamin West’s most notable history paintings, Penn’s Treaty was popularly disseminated via both prints and copper-plate-printed textiles (or toiles). Reproduced as a quilt, the top was pieced in a framed center-medallion format, with the design centered on a large square set within a series of surrounding borders. The quilter worked from the center outward, adding borders until reaching the desired size. Similar surviving quilts attest that this was the most popular composition for high-style, fancy quilts in the Chesapeake region during the Early Republic period.

All told, Martha’s Penn’s Treaty quilt contains at least 20 different printed or painted fabrics. Most appear to be English prints, and a few may be imported Indian chintzes. They are cut and pieced into diamonds, triangles, stars, and pinwheels, and the quilting is artfully laid out in scrolls, stylized flowers, and fleur-de-lis, and chevron borders. At least one of the fabrics, a red-and-blue printed plaid, is also found in a surviving garment, a banyan, or dressing gown, once worn by George Washington. Several of the fabrics also appear in the other two surviving quilts, and they raise the intriguing question: Do the quilts present a sampling of fabrics worn in the Washington household or used in its furnishings? Perhaps, but further analysis is needed of the fabrics’ sources and dates before we can declare these quilts to be the Rosetta Stone to Mount Vernon’s fashions and interiors. At the very least, they document a range of textiles available to elite American consumers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Analysis of the sewing threads and stitches might one day enable us to estimate how many hands participated in the quiltmaking. Two of the possible contributors were nieces of Mrs. Washington: Frances Bassett Washington Lear and Frances Dandridge Henley Lear, who were respectively, the second and third wives of George Washington’s secretary Tobias Lear. Both nieces (both nicknamed Fanny) spent extended time at Mount Vernon in the 1780s and 1790s, and both would have observed, and most likely joined their aunt in her needlework. Someone else present at Mount Vernon during this period, and a possible contributor to the quilt, was Mrs. Washington’s adopted granddaughter, Eleanor (Nelly) Parke Custis Lewis. Letters and reports also document that Mrs. Washington relied on Caroline Branham, Charlotte, Alice, and Alley, the enslaved seamstresses at Mount Vernon, for certain articles of clothing and accessories for the Washington household, and this may at times have extended to working on the quilts as well. Finally, visiting female family and friends may also have lent a hand in its creation.

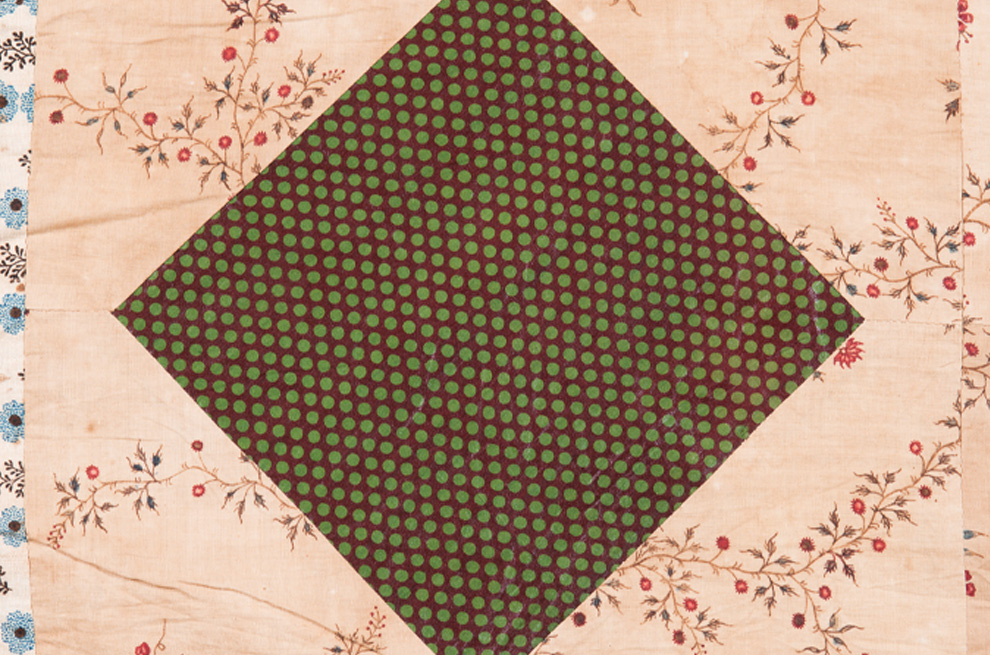

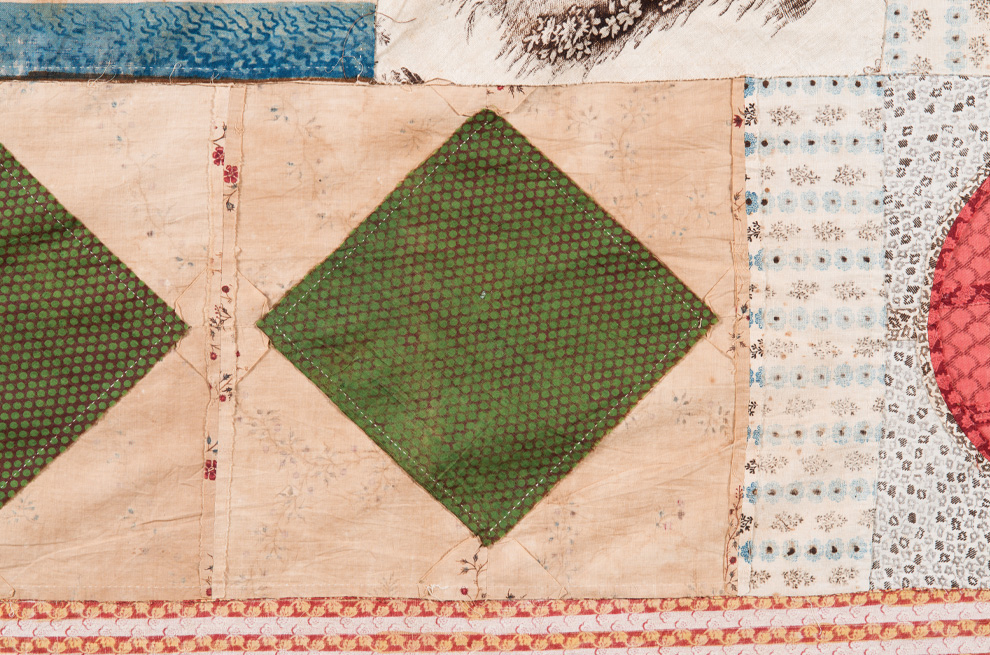

The Children’s Games top, pieced by Mrs. Washington but never quilted, is the most vibrant of her works. Granddaughter Eliza Parke Custis Law inherited it and carefully packed it in a trunk with other Washington garments and accessories. Protected from light and pests for more than a century, it retains its luminosity, incorporating 19 patterns in a rainbow of colors: sunflower yellow in hourglass blocks, rich purple in the squares near the center, mesmerizing blue stripes, deep green polka-dot diamonds, and cherry-red globes in the outer borders. Several of the fabrics sport their original glazed finish, giving the quilt a shimmer of contrasting surfaces.

Four large-scale printed vignettes in each corner give the top its name, and are taken from c. 1795 English furnishing fabric with scenes of children’s games. The top incorporates fabrics from a range of periods, including a delicate Indian painted cotton chintz from around 1770. Mrs. Washington clearly valued the imported textile and its workmanship. A dress of this same fabric fashioned in a style of c. 1810, likely its second or third generation of use, is also in the Mount Vernon collection, and attests to the care she took with such precious materials.

Because this pieced top was never quilted, it provides a rare opportunity to examine the backside, and to take a closer look at the skill of the cutting and stitching. Last year, Mount Vernon invited expert quilter Cecilia Ann Marzulli to reverse-engineer and re-create the quilt top using modern fabrics to simulate the visual effect of the original. After analyzing the quilt’s construction, Marzulli observed: “Martha was a person of great precision. She accurately cut her fabric to enhance the design depicted. Today we call this attention to detail ‘fussy cutting.’” When it is finished later this year, Marzulli’s quilt top will go on exhibit to raise awareness of Mrs. Washington’s work and funds for the conservation of the three quilts.

The third quilt by Mrs. Washington, a recent gift to Mount Vernon, is the most dynamic of the three. Appliqued circles on the center diamond, borders, and inner corners create repetition and movement, while inward-pointing triangles act like arrows, drawing the eye back to the center. The neoclassical swags, near the outermost border, lend a harmony to the robust rhythm of the appliquéd motifs. As with Mrs. Washington’s other quilts, this one incorporates at least one known Washington dress textile—a printed and woven stripe. The bodice of the dress made from the fabric and worn by Mrs. Washington still survives, also preserved by granddaughter Eliza Law. Mrs. Washington died without completing the top, but as Eliza Law explained in a note accompanying it: “This Quilt was entirely the work of my grandmother as far as the plain borders. I finished it in 1815 and leave it to my Rosebud [Law’s granddaughter, Eliza Law Rogers].”

In addition to the quilts, two sets of quilting frames owned by Mrs. Washington survive in private collections. Both were listed in the inventory of household goods from the Mansion taken after her death, and were likely the work of the plantation’s indentured and enslaved carpenters. The largest frame can extend to accommodate a 9' x 11' quilt, and may have been used for the Penn’s Treaty quilt. The smaller frame fits a 5.5' x 7.5' quilt. No quilts of this smaller size by Mrs. Washington are known, but the presence of multiple frames suggests that there may have been more quilting activity at Mount Vernon beyond the three.

Mrs. Washington’s quilts place her within a larger quilting community in Virginia and the Mid-Atlantic during the 18th and 19th centuries, one that emerges as we look beyond her own work to that of other members of her family and community. One of the earliest quilts in the Mount Vernon collection—a rare, double-sided silk patchwork—links two generations of Dandridge women through its fabrics—Francis Orlando Jones Dandridge and her daughters, Martha Dandridge Custis Washington, Anna Maria Dandridge Bassett, and Elizabeth Dandridge Aylett Henley. Additional surviving quilts or documentary references attest to the quilting of granddaughter Martha Parke Custis Peter and nieces Martha Washington Dandridge Halyburton and Frances Ann Washington Ball. Add to that the still unknown quilting hands of many other women who may have worked with Mrs. Washington, whether at her home or another’s, whether a few stitches or many—and the network, or patchwork, of relationships widens. For historians, quilts offer tantalizing threads of information that lead to an understanding of social connections and relationships that might otherwise go undetected. For at its core, the process of quilting is intrinsically about stitching together diverse people, materials, and concepts to create a new unity—e pluribus unum.