What do the presidential portraits of George Washington say about him, the artists who depicted him, and the country he helped build?

A story in pictures

Although George Washington lived more than 200 years ago, virtually everyone today knows what he looked like—his face by Gilbert Stuart enshrined on the one dollar bill. Yet Stuart was only one of several artists who portrayed Washington from life during his presidency.

Unlike European monarchs, Washington did not commission an official state portrait to proclaim and legitimize his accession to office. Artists, therefore, faced an unprecedented challenge: How to conceptualize and represent an entirely novel public figure—an ordinary citizen who embodied a fragile national identity, but was only temporarily invested with power by the will of the people?

A sampling of presidential portraits in the Mount Vernon collection showcases the variety of images that resulted. Some artists continued to depict Washington as a uniformed military commander, despite the explicitly civilian nature of his new job. Others envisioned him as a classical hero, the American Cincinnatus, a man of the ages embodying ancient republican ideals. Only gradually did a vision of the contemporary civilian statesman emerge, effectively uniting the traditional format of state portraiture with Washington’s personal features and the emblems of the new American republic.

George Washington, by Anne-Flore Millet, Marquise Jean-Françoise-René-Almaire de Bréhan, ink and watercolor drawing on paper, 1788–1789. MVLA, W-2508.

American Cincinnatus

On October 3, 1789, George Washington recorded a visit by the French noblewoman Madame de Bréhan. She came “to complete a Miniature profile of me which she had begun from Memory and which she had made exceedingly like the Original.” That “original” was a plaster bas relief by Joseph Wright of Philadelphia, depicting Washington in the style of an ancient Roman medallion portrait, with, as befit the American Cincinnatus, his head encircled by a laurel wreath—a classical emblem of victory. De Bréhan had evidently seen and copied the Wright profile when she and her brother-in-law, the French minister the Comte de Moustier, visited the Washingtons at Mount Vernon in the fall of 1788. One of only two known life portraits of Washington created by a female artist, de Bréhan’s likeness was intended primarily for private circulation and has remained relatively little known. She presented this watercolor (one of a handful she made) to Washington, who in turn presented it to Anne Willing Bingham, one of the social mavens of federal-era Philadelphia.

Online: Learn more about Joseph Wright’s plaster medallion portrait bust of George Washington crowned with laurel, the American Cincinnatus, 1783–1785.

Military Profile

Despite the explicitly civilian nature of Washington’s new office, many presidential portraits continued to depict him in his old Continental Army uniform. Joseph Wright’s likeness shows the commander in profile, the sharply defined features and determined expression conveying strength of character, resolution, and leadership. The son of internationally celebrated wax sculptress Patience Wright, and the first American student admitted to London’s Royal Academy of Arts, Wright had modeled Washington from life at the end of the Revolution. From that sitting, the Philadelphia artist created two distinct likenesses: a realistic, even harsh, painting of the war-weary general and the laurel-crowned bas relief bust copied by Madame de Bréhan. Early in the presidency, Wright combined these images, modernizing the classical bust with an authentic uniform and adding a few years to Washington’s apparent age. The 1793 yellow fever epidemic cut short Wright’s career, but his Washington profile lived on—in part because it was easier to copy than more three-dimensional likenesses. It graced medals, tokens, broadsides, magazine illustrations, sheet music, ceramics, and textiles well into the 1810s.

Online: See Joseph Wright’s oil portrait of a war-weary commander in chief, 1783.

George Washington, after Joseph Wright, from the Massachusetts Magazine, 1791. MVLA, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Stanley DeForest Scott, 1985, SC-120.

George Washington, Washington Before Boston Medal, die engraved by Pierre Simon Benjamin Duvivier, after Jean Antoine Houdon, bronze, 1789.MVLA, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Stanley DeForest Scott, 1998, M-4012.

French Perspective

Given the level of manufacturing skills and production facilities in the infant United States, portraits in certain media—high-quality engravings, medals, sculpture—had to be commissioned from specialized artists and artisans in European urban centers, a complicated process that frequently caused years of delays. The internationally renowned French sculptor Jean Antoine Houdon had come to Mount Vernon in 1785 to sculpt Washington from life, producing an undraped clay bust that many regard as the preeminent Washington portrait. Few Americans had an opportunity to view Houdon’s version of Washington until the spring of 1790, when Thomas Jefferson arrived from France carrying examples of this medal. Struck by the Paris mint in fulfillment of a 1776 congressional commission, it featured a low-relief version of Houdon’s bust in profile.

Online: View Jean Antoine Houdon’s original 1785 clay bust of Washington in 360°.

George Washington, engraved by William Hamlin, after Edward Savage, mezzotint, c. 1800. MVLA, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Stanley DeForest Scott, 1985, SC-89.

Presidential Look

A self-taught but ambitious New Englander, Edward Savage was an innovator in the creation of patriotic imagery and an explicitly “presidential” portrait. In the first year of Washington’s administration, Savage persuaded Harvard College to award him a commission to paint Washington, which he did—in military uniform. Four years later, in London, Savage created the first significant print to depict the chief executive in civilian garb: a mezzotint in the tradition of English gentlemen’s half-length portraits, enhanced with some of the trappings of formal state portraits associated with European monarchs—a portico-like space with a wall, column, drapery, and an open sky—as well as specific attributes of the American president—the elegant black velvet suit and a plan of the future federal city. This copy was engraved by Rhode Island artist William Hamlin, after Washington’s death.

Online: Discover Edward Savage’s initial portrait of Washington in uniform, engraved in 1792.

George Washington, by Massimiliano Ravenna, after Giuseppe Ceracchi, marble, c. 1816. MVLA, M-5824.

Italian Hero

Giuseppe Ceracchi was one of many immigrant artists who flocked to the new American nation seeking fame and fortune. Aiming at a congressional commission for a grand equestrian monument, Ceracchi secured a sitting with Washington in the winter of 1791–1792. He thus became the only sculptor to model George Washington from life during the presidency. Ceracchi’s Washington is a strong and virile hero—younger than the subject’s actual 60 years. The artist replaced Washington’s customary queue, or ponytail, with a close-cropped, curly Italian hairstyle that evokes the classical hero and the ideals of the Roman republic. Thomas Jefferson praised the result as “the best effigy of [Washington] ever executed.” This bust is one of a handful of marble copies of Ceracchi’s original terracotta bust, carved in Italy around 1815; James Madison’s administration acquired a nearly identical one for the White House, where it remains today.

See it: In the presidential section of the Education Center galleries.

George Washington, by Walter Robertson, watercolor on ivory, 1794. MVLA, Courtesy of Stewart P., Cameron B. and Brian H. McCaw, W-2565/A.

Family Keepsake

Given that George Washington sat for nearly two dozen different artists over the course of his life, it is striking that he personally initiated the creation of only one likeness. Granting a request from his step-granddaughters, he commissioned portraits from the Irish miniaturist Walter Robertson in the fall of 1794. “I have no other wish nearer my heart than that of possessing your likeness,” wrote 18-year-old Eliza Parke Custis, “it is my first wish to have it in my power to contemplate, at all times, the features of one, who, I so highly respect as the Father of his Country and look up to with grateful affection as a parent to myself and family.” Robertson’s delicate miniatures were intimate and personal, set in lockets for close family, and not intended for public display. Nonetheless, within months the likeness appeared in an ambitious engraving embellished by an array of both patriotic and classical symbols, including a federal eagle, scales of Justice, sword, liberty cap, and laurel wreath.

Online: Discover a London engraving of Robertson’s Washington portrait, 1797.

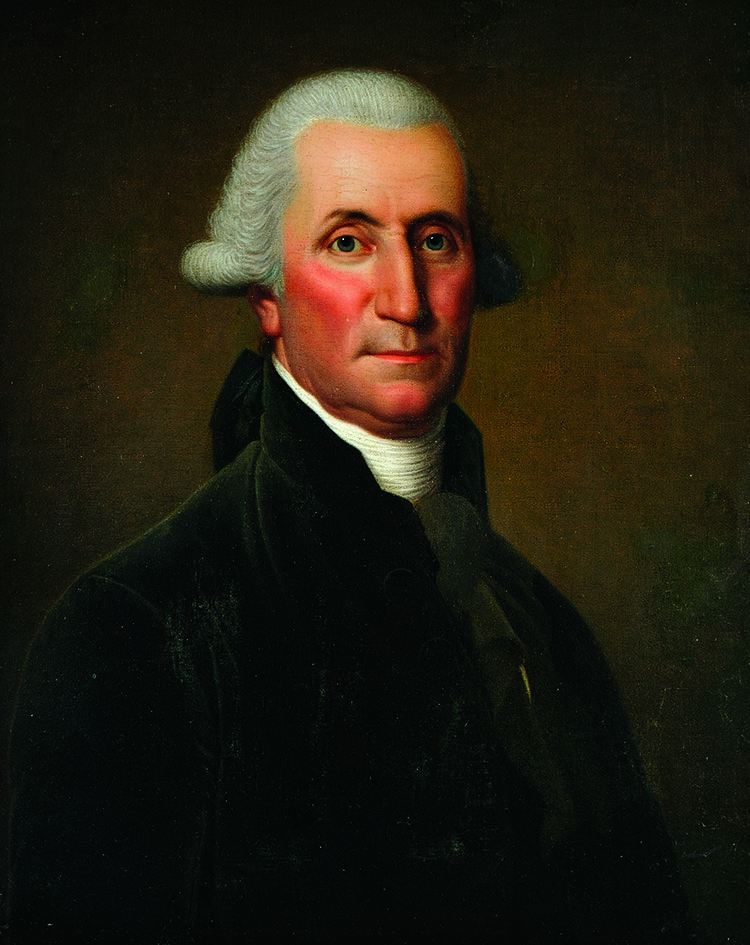

George Washington, by Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller, oil on canvas, 1794–1795. MVLA, Purchased by the Connoisseur Society of Mount Vernon, 2011, H-4902.

Aristocratic Gentleman

Before arriving in America in early 1794, Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller had enjoyed appointments as royal painter to the courts of Sweden and France. At Versailles, he had made the mistake of painting Marie Antoinette too casually, strolling in the gardens with her children. He did not make the same mistake with George Washington, depicting the president with austere formality and aristocratic dignity. The direct gaze conveys a vitality and force of character, balanced by the barest hint of a smile—one of the few to be seen in Washington’s many portraits. One would hardly guess from the calm of the portrait, that during the time Wertmüller painted, Washington was deep in the throes of the Whiskey Rebellion, one of the most critical tests of his presidency.

See it: In the Museum galleries.

Portrait In Silk

The second of two women who produced surviving life portraits of George Washington, Ellen Sharples arrived in America from England in 1794 with her husband, portraitist James Sharples, and their three young children. Hoping to establish a lucrative business creating and selling small, inexpensive pastel portraits of eminent Americans, the enterprising couple secured a sitting in the spring of 1796. From it, they together produced more than two dozen pastel replicas. Ellen demonstrated her own artistry in this unique portrait, translating the colorful medium of pastel into an exquisite black on white silk embroidery—a difficult genre of needlework called “printwork” for the obvious reason that it imitates the dots and lines of an engraving. Plying her needle with great skill, Sharples created a sensitive and compelling characterization of Washington, the artistic equal of many contemporary oil paintings and prints.

Online: See one of numerous examples of the Sharples’ pastel portrait of George Washington, c. 1799.

Detail of George Washington, by Ellen Sharples, after James Sharples, silk embroidery on silk, c. 1797. MVLA, Gift of Mrs. John R. Tomlin, 1902, H-630.

Why It Matters

As America’s first president, George Washington established many precedents, one of which was not authorizing an official view of the head of state. Precisely because no standard likeness emerged during his lifetime, there has been room for alternate visions of what a republican chief executive should or could be. This represents a distinctively participatory—even “democratic”—process for creating national iconography. More than two centuries after his presidency, George Washington’s visage continues to play a pivotal role in America’s image of itself, its history, and its future.

Discover more about all these portraits and related art online: mountvernon.org/presidentialportraits

Susan P. Schoelwer is the executive director of historic preservation and collections and Robert H. Smith Senior Curator at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. She has directed the ongoing refurnishing and reinterpretation of Mansion rooms and the greenhouse slave quarters, as well as museum exhibitions, including the award-winning Lives Bound Together: Slavery at George Washington’s Mount Vernon She is working on a book on George Washington portraits.

Header image: George Washington (“Lansdowne” portrait), Gilbert Stuart, 1796. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.