NEW RESEARCH

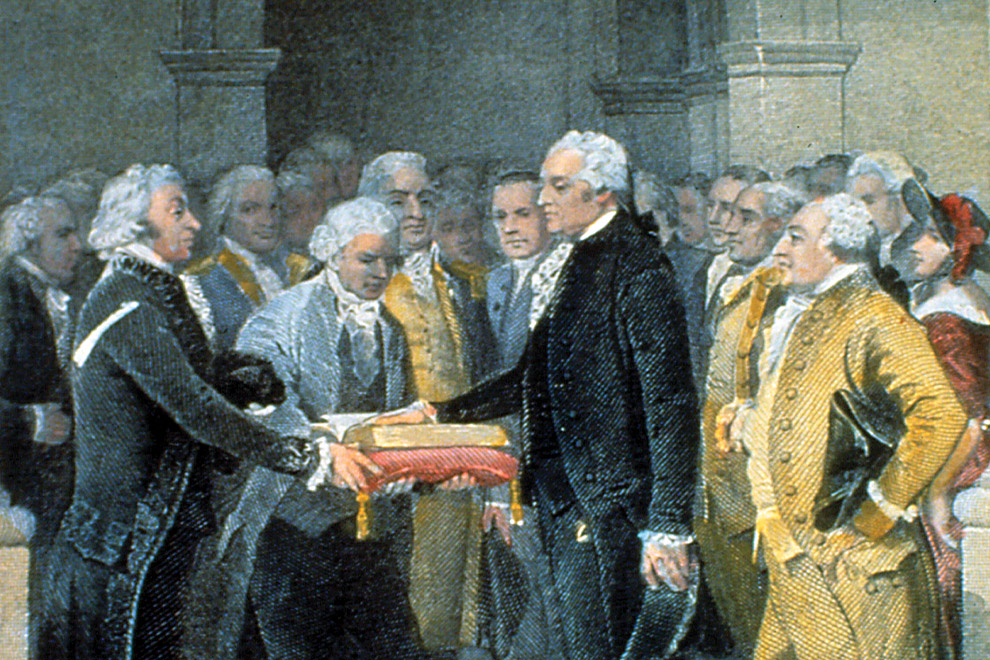

Illustration of Washington, after Zlonzo Chappel, 1859, MVLA

The Real Story Behind Washington’s

“Unanimous” Election

In the spring of 1789, George Washington won the first ever election to the U.S. presidency unanimously, meaning that electors from every participating state cast at least one of their votes for him. For 21st-century observers, the unanimity of Washington’s election may make his ascent to the presidency seem noteworthy, if only to illustrate the quirkiness of the Electoral College. To avoid the possibility of a deadlocked election in the event electors chose candidates from their home states, the Constitution specified two ballots, one of which had to be cast for someone outside the elector’s home state. Because every elector cast at least one vote for Washington, his election was deemed unanimous. Yet commentators at the time often described the act as a statement of approval by “millions” of Americans, not just electors. Far more than a well-deserved honor for a virtuous man, Washington’s unanimous election attests to the crucial role the public played in turning the presidency into a cultural symbol of the new nation: who counted as an American, who did not, and what bound them to each other and to their government.

Though the requisite nine states ratified the Constitution by the summer of 1788, that document stipulated that the new government would govern only the ratifying states. Evidence of division, and doubts that a country as large as the United States could ever be unified, were everywhere. Two states, Rhode Island and North Carolina, had still not ratified the Constitution. Washington’s election could potentially reassure wavering citizens of the strength of the national bond. But the victory would have to be unanimous.

A newspaper from New York, anticipating the offense that Washington’s future vice president, John Adams, might take, revealed the importance of a unanimous election when it sought to explain why there was no shame in being the runner-up. It was, the piece assured readers (and Adams), “an honor, merited by few men, in being second to our beloved Washington in the affections and esteem of the people of the United States.” Statements like these construed Washington’s ascent as proof that the nation was unified by a shared confidence in him and, by extension, the new government he would lead.

While, as already noted, the country’s newspapers often described Washington’s election as the choice of millions, others used a specific number—three million—the approximate number of free citizens in the country, according to the census conducted by Congress in 1790. This characterization sidestepped the realities of the Electoral College, and implied that Washington owed his ascent to more than just those who could formally cast a vote.

For his part, Washington’s actions reinforced that inclusive message. He undertook two ambitious tours of the country early in his presidency, and from town to town, according to reports, he was met by adoring women, as well as starry-eyed children and cooing babies who lacked the ability to vote but who nevertheless added to the chorus of confidence. One observer wrote to his nephew that Washington’s reception in late April 1789 in New York was attended by “more than twenty thousand free citizens, who lined every fence, field and avenue between the bridge and city.” This included “the aged Sire, the venerable Matron, the blooming Virgin, and the ruddy Youth,” all of whom expressed their support for the president-elect. Even “the lisping Infant did not withhold its innocent smile of praise and approbation.”

Of course, enslaved persons had no say in the matter, though the actions of some of those enslaved by the Washingtons demonstrated that not everyone assented to the first president’s authority. During his presidency, George Washington’s enslaved cook, a man named Hercules, and an enslaved woman named Ona Judge, who served as Martha Washington’s personal attendant, would separately escape to freedom. Hercules and Ona Judge, as well as the nearly four dozen other persons who attempted to escape the Washingtons’ authority during the last 39 years of George Washington’s life, were not counted as part of the single national “people” envisioned by celebrants of Washington’s unanimous election.

The omission extended beyond enslaved black persons to include nonwhites more generally. Though some states did not deny free black people the right to vote, legal codes and social custom over more than a century and a half effectively did. By the end of the 18th century, the vast majority of whites understood that freedom in its fullest sense was reserved for them alone. Washington himself said as much during the American Revolution, when he noted that if Americans refused to resist British “Measures,” they would become “tame, & abject Slaves, as the Blacks we Rule over with such arbitrary Sway.” In the coming years, as black Americans sought to assert their own claims to citizenship, white commentators on the presidency would spell out what celebrators of Washington’s “unanimous” election took as a given: that the nation the president embodied, and to whom he would be accountable, was white.

Much has changed from Washington’s time to our own. Yet to this day, the presidency remains far more than a government office. It is the cultural symbol of “the people,” a role that was not the invention of presidential incumbents alone. Indeed, others were crucial in making the office the touchstone of the American nation, reflective of our highest ideals, as well as our most entrenched prejudices. In that sense, the story of the unanimous election of 1789 is an important early chapter in American history: a story whose impact echoes beyond the first president’s time into our own.

Nathaniel C. Green is a professor of history at Northern Virginia Community College. He was a Fellow at the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon in the summer of 2015. This piece is adapted from his book The Man of the People: Political Dissent and the Making of the American Presidency (University Press of Kansas, 2020).