The father of American architecture pays a visit to the father of the country at Mount Vernon

On a hot July morning in 1796, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, a recent immigrant from England, arrived by horseback at Mount Vernon, hoping to meet the president of the United States and perhaps spend an hour or so with the most important man in America.

Latrobe had been in the United States for only a few months, but given the fluid nature of relationships in the new nation, he had quickly become friends with Bushrod Washington, the president’s nephew, who lived in Richmond. Now he carried Bushrod’s letter of introduction to Washington, who appeared after 10 minutes and, as Latrobe recorded in his journal, “shook me by the hand and said he was glad to see a friend of his nephew’s. He inquired over family I had left [in England] and the conversation turned to Bath” (Berkeley Springs), where he and Mrs. Washington planned a future visit.

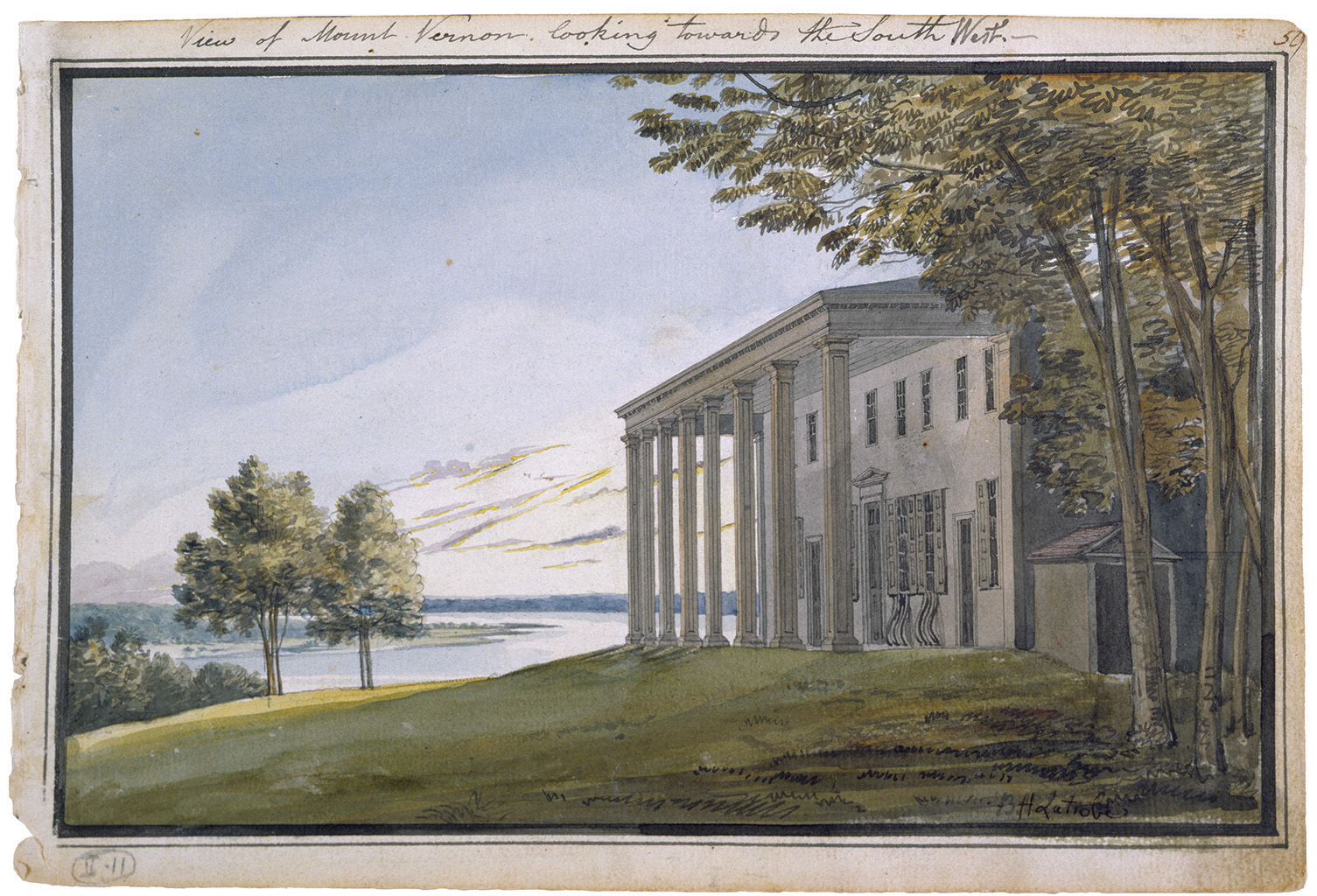

Above: Entitled The View of Mt. Vernon Looking Towards the South West, this watercolor by Benjamin Latrobe is one of two similar works, one of which he presented to Washington. Here the young architect includes both the manor house and the broad vista across the Potomac River.

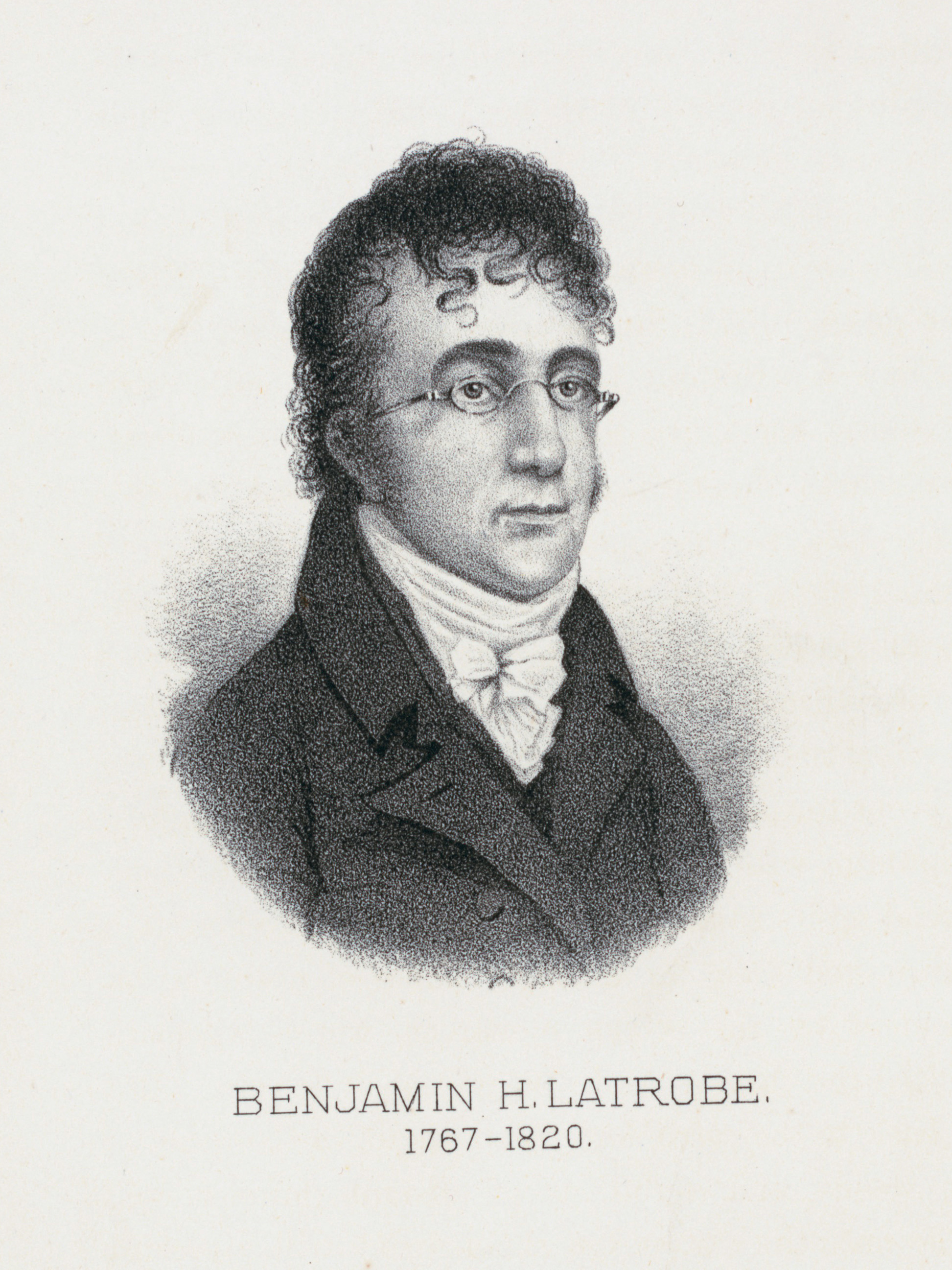

Latrobe (opposite, in a portrait on ivory by Raphaelle Peale) was impressed with how Washington had enhanced the setting of his estate by trimming trees and clearing the lawn. That improved view was prominent in View of Mt. Vernon Looking to the North (preceding pages).

Rather than the few hours Latrobe anticipated spending at Mount Vernon, he spent the night, at Washington’s urging, and enjoyed dinner, evening coffee, a hearty breakfast, and multiple conversations with the president and his family. Latrobe recorded his visit in detail in his journal, thereby furnishing a rare early account of Mount Vernon. The 32-year-old architect—who in less than a decade would be designing major projects in the new nation’s capital—also used his talents as an amateur artist to produce several sketches and four memorable watercolors of the grounds and house.

The two men talked about such prosaic matters as the rivers of Virginia, the Hessian fly, and the Rotherham plough that Washington could not get repaired and Latrobe promised to replace. Unlike the king and aristocrats of Great Britain, the president was not haughty. He listened to what Latrobe had to say: “I was much flattered by his attention to my observations and his taking pains to object to my deductions where he thought them ill-founded and to confirm them by very strong remarks of his own while he was in agreement.” Clearly, the president declined both the regal postures and the lavish settings familiar to Latrobe in Georgian England. And yet, according to Latrobe, “there was something uncommonly majestic and commanding in his walk, his address, his figure and his countenance.”

One of the first formally trained professional architects in the new United States, Latrobe had expected to be as awed as he had been when he’d briefly encountered Frederick the Great in Prussia. Instead, he found simplicity and a level of egalitarianism. In fact, Washington personified the reasons Latrobe had left a monarchy for a republic. Here, on this Virginia estate, was one of the greatest men “that Nature had ever produced,” a public man who surrendered his leisure for service, a leader of “exceptional humanity,” a president who fulfilled the poet Horace’s definition of “the great man whose mind on virtue spent/Pursues some great goodly intent.”

These meetings with Washington and Latrobe’s reaction to Mount Vernon and the surrounding landscape provided early instruction in the democratic ways of his new country. For Latrobe, whose neoclassical architecture would soon define both the public and private buildings of the United States—including the U.S. Capitol—the hospitality of the president toward an unknown émigré confirmed his expectation that the United States was a nation of promise with permeable social boundaries. Even Washington’s residence, no better in Latrobe’s view than that of an English country gentleman, confirmed the lack of aristocratic pretension. In America, as a man “head and ears in love with Man in a state of Nature,” Latrobe might actually find “the dawn of the Golden Age itself.” In this new country, a talented architect and engineer could get ahead on his merits and establish himself professionally. In England, given the number of talented architects (it was, after all, the great age of Georgian architecture in England), he had not been certain that would be the case.

Latrobe was born in 1764 and raised in Fulneck, an English Moravian community that discouraged parental contact. As a young man, Benjamin Henry Latrobe rejected the church in which he had been raised. He rebelled against his father and his elder brother, who expected him to follow them into the ministry, and was expelled from training schools in Germany. He moved to London, where he found his calling studying architecture and engineering with the best of Britain’s professionals, including Samuel Cockerell, and received several commissions for private homes during his 13 years there. When his wife died in childbirth and he found himself in debt, he left England at the age of 32, arriving in the United States in the spring of 1796, four months before his visit to Mount Vernon.

During that visit, it was not only the president but also the house and its surroundings that impressed Latrobe. A close observer, he described the estate in his journal—its neatness, its good fences, and its cleared grounds, as well as the natural vistas framed by “bold woody hills,” with their abundance of trees that made the landscape so notable for émigrés from a more developed England. Washington had improved the natural landscape with a lawn on the east side of the house that sloped down toward the Potomac River, and the trees and shrubs were trimmed. The view was impressive and indicative of a country where “Nature had lavished magnificence…”

In addition, Latrobe described the lawn on the west side of the house, with its formal serpentine walk shaded by weeping willows that flourished in the eastern United States. There was “a plain kitchen garden [and] a neat flower garden laid out in squares, and boxed with great precission. Along the North Wall of this Garden is a plain Greenhouse.… The Plants were arranged in front, and contained nothing very rare, nor were they numerous.” He also discovered a “parterre chipped and trimmed with infinite care in the form of a richly flourished Fleur de Lis.” No doubt, though Latrobe did not say so, the horticultural arrangement honored the nation’s French allies during the American Revolution and especially paid tribute to the Marquis de Lafayette, now languishing in a French prison but whose 17-year-old son, Georges Washington Louis Gilbert Lafayette, was currently a guest at Mount Vernon. Overall, the grounds were symbolically American: plain and unpretentious, and lacking the formality Latrobe had observed surrounding the grand houses of England’s aristocracy.

Above: In “Sketches of George Washington”, Latrobe tried to display what he considered the president’s physical power—a man he described as “uncommonly majestic in his walk, his address, his figure and his countenance” (Library of Congress & MVLA)

As for the house itself, it disappointed Latrobe, although he believed that it characterized the nation’s tastes. The main portion of Mount Vernon—its wooden exterior painted a champagne color—was not imposing. The center was merely “an old house to which a good dining room had been added at the North end, and a study &c. &c., at the South.” The handsome chimney piece in the dining room was “the only expensive decoration I have seen about the house. Everything else is extremely good and neat, but by no means above what would be expected in a plain English Country Gentleman’s house of 500 or 600 pounds a year.” Overall, the home of America’s hero was undistinguished, in keeping with a new republic where the people, and not the monarchy, were sovereign. Still, Mount Vernon was certainly a little “above” those estates he had previously seen in his travels around Virginia. And for the rest of Latrobe’s life, Washington the man served as the heroic embodiment of national virtues, while the president’s home came to represent the philistine tastes and culture of the United States.

Before he left, Latrobe strolled about the grounds with his sketchbook, and the resulting four watercolors have become the definitive views of Washington’s estate during his lifetime. (Latrobe also sketched a silhouette of Washington, and several views of the house appear in his journal.) In all four of the finished watercolors nature predominates; the house is obliquely seen, almost as a framing device. The vista across the water made an impression on the young visionary; it was the unknown America of the future.

In the watercolor View of Mount Vernon looking toward the South West, which Latrobe intended as a gift to Washington for his hospitality, he painted in family members—including Martha Washington—gathered around a tea table on the piazza. Latrobe found the first lady, like her husband, without “the affectation of superiority. She acts completely in the character of the Mistress of a respectable and opulent country gentleman.” In the scene, everyone, including Eleanor Parke Custis, the president’s handsome step-granddaughter, faces the river, away from the house. It is easy to see in Latrobe’s depiction a metaphor for his own uncharted future.

Three and a half years later, in December 1799, Washington died. Latrobe was among those who mourned the loss of an American hero. A special congressional committee convened to determine the proper memorial for the esteemed father of the country. Some favored an equestrian statue in front of the U.S. Capitol, while others lobbied for a marble obelisk. Latrobe, now living in Philadelphia, complained that marble statues broke too easily; one had only to remember the maimed statues of antiquity. In fact, a statue of Washington in Richmond, Virginia, had already lost several small parts. Bronze was sturdier, but its appearance was stiff and disagreeable. Latrobe submitted a design for a pyramid made of granite, because “a monument erected to the memory of the Founder of American Liberty should be as durable as the Nation that erected it.” The interior would hold Washington’s tomb, and there would be bas-reliefs or frescos of the principal events of Washington’s life on the walls. But Congress dithered, and it would be nearly a half century before the Washington Monument was even begun.

Given his broad practice, Latrobe’s buildings and his engineering projects affected every aspect of life in the early republic—its worship, governance, communication, education, and domesticity. His neoclassical style for public buildings was reproduced throughout early America, and his engineering projects brought clean water to America’s cities. As the best architecture does, his designs conveyed an inspirational message to his new countrymen and women about the worthiness of their great experiment.

As his own influence on the built environment of the United States increased, Latrobe grew increasingly critical of George Washington’s aesthetic standards. The president had approved a flawed design for the U.S. Capitol that Latrobe had to correct; unfortunately, he could only do so in a way that conformed to the president’s (or what Congress considered to be the president’s) plan. Further, Washington had done little toward the development of the new capital and had purchased only a few inferior lots in the District of Columbia.

To Latrobe’s thinking, “General Washington knew how to give liberty to his country, but was wholly ignorant of art.” It was a judgment whose roots went all the way back to that first visit to Mount Vernon in July 1796.

Above: This watercolor by Latrobe portrays the pyramidal monument that he created to honor Washington after his death in 1799. On the interior, the architect intended panels with allegorical scenes of the American hero’s life. It was never built. (Library of Congress)

Jean Baker is the Bennett Harwood Professor Emerita of History at Goucher College. Dr. Baker is the author of 11 books, including Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography, The Stevensons: The Biography of an American Family, and most recently, Building America: The Life of Benjamin Henry Latrobe.